At the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference (COP21), nearly all the countries of the world committed to keeping the global temperature increase below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial times, but aiming to limit warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius. But how can the world achieve this goal and what happens if the global average temperature increases to 1.5 degrees? This is what the world's leading climate organization, the IPCC, has tried to answer in a special report released yesterday. The report sends a message that has never been clearer: keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees will be very difficult, but the alternative is not an option and we must act now.

Today, the scientific understanding, technical capacity and financial means exist to tackle climate change and avoid 1.5 degrees of warming. The transition will also bring enormous benefits, both economic and social, to those who make it. But it will require major systemic changes in technology and behavior in all areas and will require stronger and more comprehensive commitments from the world's countries. And it will have to be done in an unprecedentedly short timeframe. Johan Rockström, Professor of Environmental Science at the Strockholm Resilience Center writes in an article from Aftonbladet "to have a chance to stabilize the warming at 1.5 degrees, we are in a position where we have less than 10 years left if we continue on the current course".

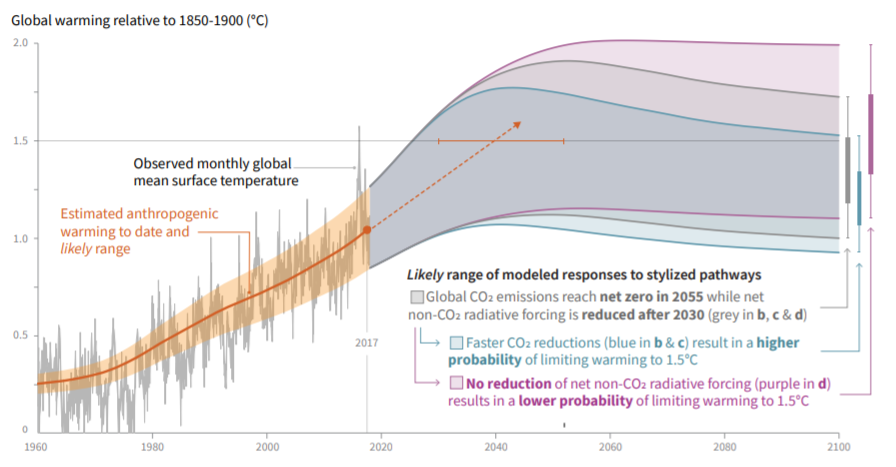

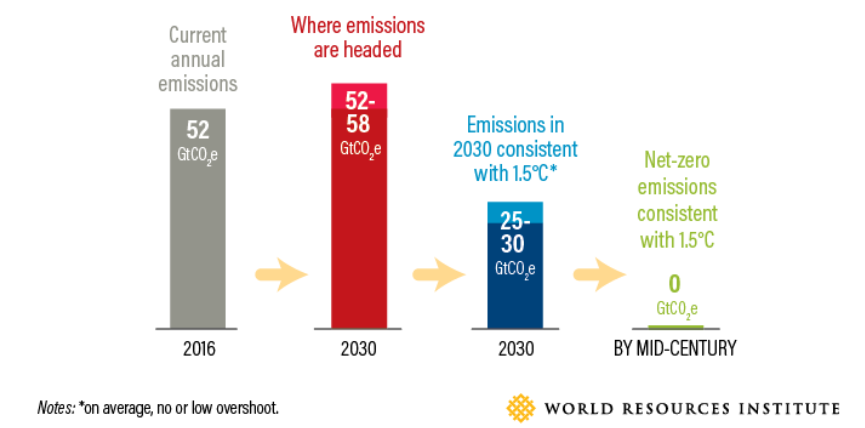

The figure below shows different scenarios for how the world can keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. To succeed, the world would need to reduce emissions by 45% from 2010 levels to reach net zero emissions by mid-century. All scenarios require a combination of emission reductions and negative emissions, i.e. sequestering already emitted greenhouse gases from the atmosphere through, for example, reforestation

Source: IPCC Summary for Policy Makers (2018)

Source: World Resource Institute (2018)

The difference between 1.5 degrees warming and 2 degrees warming

Today, global warming has led to about 1 degree of warming and at current emission rates, the world will be 1.5 degrees warmer compared to pre-industrial times between 2030-2052. Already at 1.5 degrees of warming, there will be widespread impacts on the world's ecosystems and people, which will be further exacerbated at 2 degrees of temperature increase. For example, 70-90% of the world's coral reefs are expected to disappear at 1.5 degrees, rising to over 99% at 2 degrees.

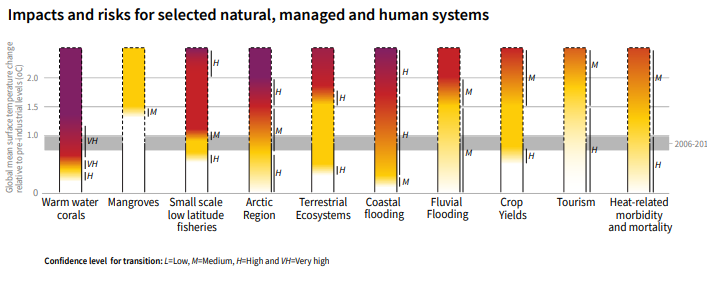

The consequences of climate change will be unevenly distributed across the globe and will hit vulnerable and resource-poor communities the hardest. The figure below shows the risk for some selected areas at different temperatures. For example, in the Arctic, where the rate of warming is about twice as fast, sea ice is expected to be ice-free in summer at 1.5 degrees of warming every 100 years, and at 2 degrees of warming every 10 years.

Source: IPCC Summary for Policy Makers (2018)

The risk of self-heating effects is underestimated

However, the IPCC report has been criticized for omitting the most devastating and difficult to understand consequences of global warming, namely the self-regulating feedback effects that risk amplifying global warming at levels well above 2 degrees. In an article published today by The Guardian, several scientists write about the risk of so-called "tipping points" that could lead to irreversible consequences and domino effects that would make human action to limit further warming futile.

Sweden, which has one of the world's most ambitious climate targets, has an important role in the transition. Sweden has reduced emissions by 26% since 1990, which corresponds to an annual emissions reduction of 2% per year. But to reach the climate target of net-zero emissions by 2045, the annual reduction must be 5-8% per year. With the world watching, we must show that it is possible to combine economic development and prosperity with lower emissions. Sweden needs to lead the way and show through research and innovation how this can be done, because if we don't, how can we expect countries with less favorable conditions to succeed?