Trees as carbon sinks

September 5, 2023

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is clear that we will need to use negative emissions to tackle the climate crisis, no matter how quickly we manage to reduce our emissions. Many people put their faith in technology and that science will be able to solve the climate issue by machine. New climate-smart technology is important, but what if there was another, often faster and simpler solution? Something that has been right under our noses all along?

The solution for an effective, cheap, large-scale method of storing carbon dioxide is trees. Ordinary trees. The trees absorb carbon dioxide, which they then convert into glucose, and in the process create oxygen as a (very welcome) by-product. Trees are about 50% carbon, plus cellulose, water, minerals and a few other things. To calculate exactly how much carbon is in a tree, only the dry mass of the tree is taken into account. Trees that have a very dense mass, i.e. contain less water, absorb more carbon dioxide because they have more of the dry mass where the carbon is stored.

How much carbon dioxide do trees absorb?

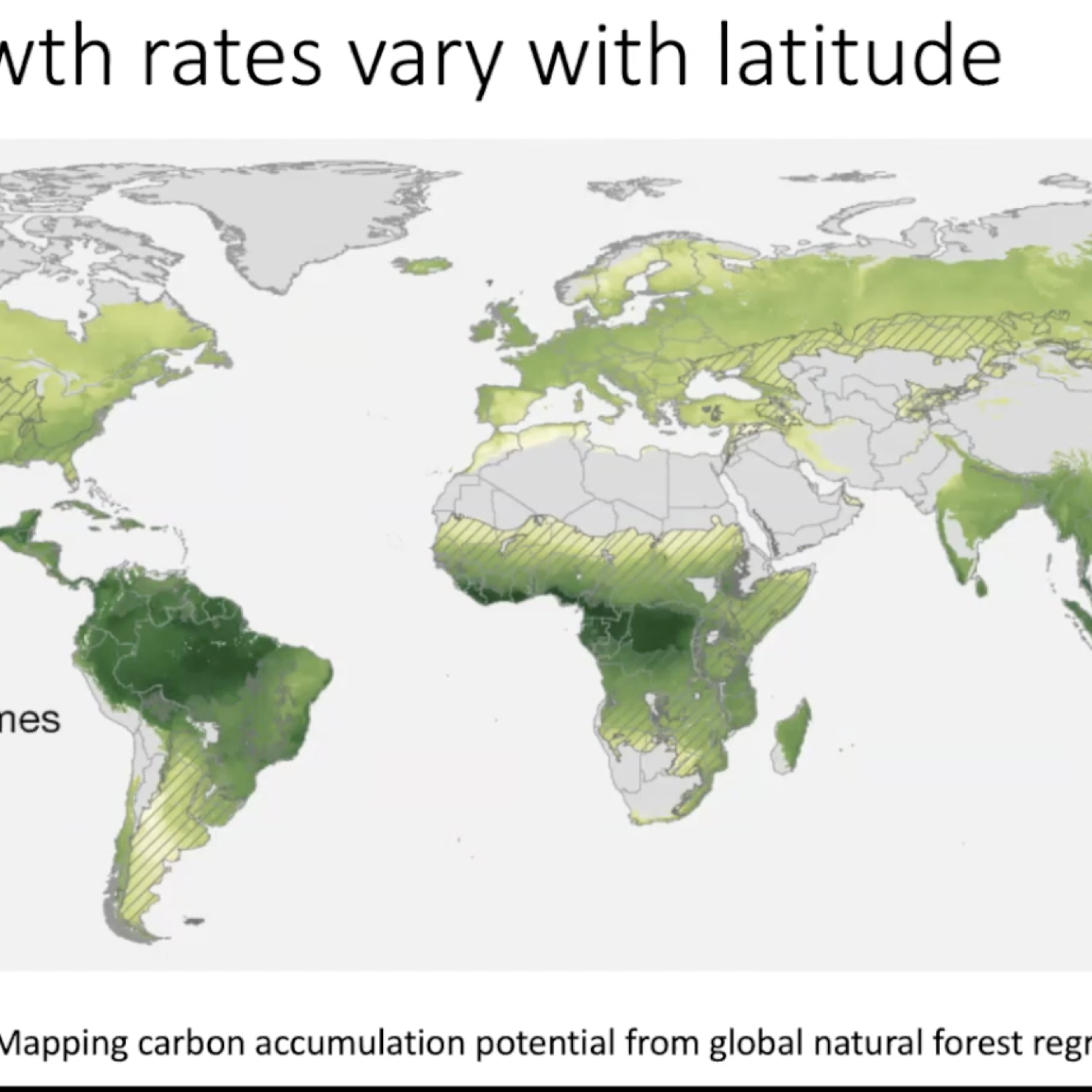

Carbon sequestration varies between tree species, the climate zone they grow in (think gnarled mountain birch), and the soil in which the tree grows. Trees in southern latitudes, where we at ZeroMission have our projects, can grow up to 10 times faster than trees growing in the northern hemisphere. How much carbon dioxide the tree can absorb also depends on its weight and how old it is. An average 35-year-old tree sequesters about 25 kg of carbon dioxide each year, but the range is somewhere between 10-40 kg per year.

Old or young trees?

Scientists disagree on whether old or young trees absorb the most carbon dioxide. Young trees grow faster, but older trees have denser wood mass. A prerequisite for achieving maximum carbon sequestration could therefore be to reward both, i.e. retain natural forests with older trees and plant new forests where there were previously none, or in areas that have been deforested. Older forests that have been allowed to grow freely and for a long time also have greater biodiversity, which is important not only from a climate perspective but also from other aspects.

Carbon balance in the forest

The annual carbon balance of forests can vary from year to year depending on factors such as solar radiation and temperature. Carbon fixation in northern coniferous forests is highest at 15-20 degrees C (i.e. spring and summer for us in the Nordic countries). In our climate, 95% of photosynthesis, and thus carbon storage, occurs during the summer months. At sub-zero temperatures, photosynthesis is close to zero. Over a longer period of time, the forest naturally absorbs more carbon dioxide than it emits, provided that the climate does not drastically change. However, on really hot days, the forest can instead emit carbon dioxide and become a carbon source instead of a carbon sink.

Old Tjikko - the world's oldest spruce (9550 years old).

Forest management and agroforestry

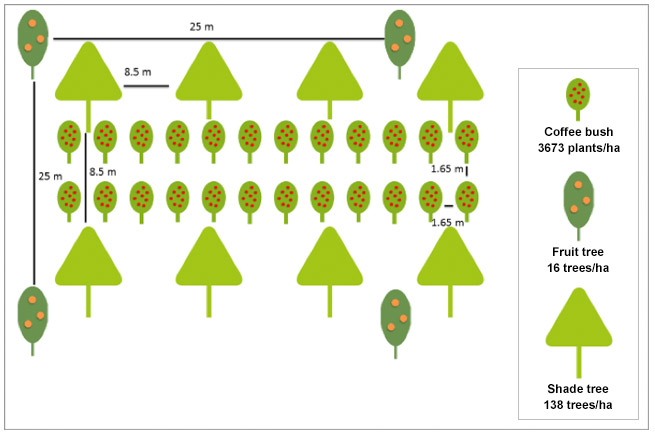

Forest management also has a major impact on the long-term carbon balance. Agroforestry plantations absorb more carbon dioxide than monocultures because the plants 'benefit' from each other, creating positive synergies. For example, in an agroforestry model, ground cover crops can be used to increase the ability of plants to prevent carbon dioxide from being released.

From the point of view of maximum carbon sequestration, relatively little or no tillage is preferable because it means that less carbon dioxide is emitted from the soil. This is why no-till farming is often highlighted as an important climate measure, which according to some researchers can contribute as much as 30% lower carbon emissions emissions globally per year. When fields are not plowed, moisture is retained in the soil, allowing plants to grow better. So it's the trees and plant photosynthesis that do the heavy lifting. No-till farming also reduces fuel consumption (and therefore emissions) and the risk of soil erosion.

Agroforestry system with trees and coffee bushes.

Are trees all we need?

No, it is never as simple as it sounds. Even carbon sequestration through tree planting has its challenges, with permanence often raised as a potential problem. In the event of a forest fire, for example, carbon dioxide risks leaking back into the atmosphere, and no one can guarantee that a forest will remain untouched for hundreds of years. At the same time, tree planting is one of the most important methods of large-scale carbon sequestration available to us and something we must not forget, while keeping our fingers crossed that the development of technical methods to store carbon dioxide also progresses. To tackle the climate crisis, we will need a Swiss army knife of solutions. And fast.

More about agroforestry?

For example, read about our CommuniTree project in Nicaragua here.

Forest carbon balance = every winter, deciduous trees drop their leaves, releasing carbon dioxide, but by summer, when the new leaves appear, the trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere again.